Timo Mueller

All other posts

A six-month reprise for the FDLR: A process doomed to fail?!?

During a public press conference on Wednesday, chief of MONUSCO Martin Kobler lamented that FDLR had interpreted a six-month timeframe to disarm or face military operations as a call to stall previously scheduled demobilizations (see transcript and media report). But as much as the FDLR willingly misunderstands the process as much was it led to conclude just that. In addition, Kobler did not admit that MONUSCO was pressured into a process it actually disagreed with from the very beginning.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) granted FDLR a respite in early July after the group had surrendered around 200 of its men as a sign of its good will (here and here). However, two months into the process, the FDLR has yet to enter transit camps in Kisangani (Orientale Province). As of recent, they refuse it altogether. Kobler rightly says that “we don’t advance much,” echoing earlier remarks by his military spokesperson.

Let’s bear in mind that …

First, the decision to grant FDLR more time was made largely by the regional bodies, leaving MONUSCO no real chance but to support it. Both sides disagree over how to handle the FDLR. This discord was obvious from the beginning: After the rebels surrendered a first batch of men, the Executive Secretary of SADC said that they are “extremely encouraged by the disarmament of FDLR members.” However, the statement of SADC stands in stark contrast to an earlier assessment by the Special Envoys, who had called the first number of surrendered combatants “insignificant.”

A few days later, on 2 July, SADC members agreed to suspend military operations for six months against the FDLR in order to give them more time to lay down their arms. Angola’s Foreign Minister – chairing ICGLR – said: “Of course there will be no military operations during the six-month period.” But just a day later, Kobler sent a different message to the rebels, specifying that the rebel group had days, not weeks, let alone months to respond to his final offer.

Unfortunately for MONUSCO, the SADC members South Africa, Malawi and Tanzania are the very countries that staff the Force Intervention Brigade, which MONUSCO would use to fight the rebels in cooperation with the Congolese army. Even though the UN Security Council recently encouraged its mission and the Government of Congo to actively pursue military action against those leaders and members of FDLR who do not engage in the demobilization process, MONUSCO has first to get a reluctant SADC on board.

It is important to bear in mind, however, that it were African countries that initiated the brigade. They wanted it, albeit for a different armed group, the M23. Like the Government of Congo, it seems as if SADC members – especially Tanzania – are reluctant to confront the FDLR in earnest.

Second, from the beginning, MONUSCO had little hope that this process might actually work in the absence of a credible threat. One offered carrots while forgetting the stick.

Third, Kobler is losing patience. After defeating the M23 just three months into his posting, he now has to realize that his earlier success was the exception rather than the norm. All the while, he has to mend relations with neighboring Rwanda, which is increasingly frustrated with the process and MONUSCO altogether (here, here, here, here, and here). His relations with Kinshasa could certainly also be better.

Fourth, Kobler is under significant pressure from New York to prove the effectiveness and usefulness of the FIB not just in the case of Congo but for UN peacekeeping around the world. Increasingly tired of the mission in Congo, the FIB is the last shot to make things work. After fifteen years in the country, MONUSCO wants to leave on a successful note.

What does that leave us with?

In less than a month, on 2 October, the six-month reprise will be re-examined. As things stand now, the FDLR will not pass the test. But that does not necessarily mean that the FIB either unilaterally or in cooperation with the army would start using force. The new UN Special Emvoy to the region Saïd Djinnit promised it would.

Before then, US Special Envoy Russ Feingold will visit Goma and Bukavu on September 10-11 and will certainly use his clout to push the agenda once again.

For more on the FDLR and the current process, have a look at the report Endgame or bluff? written by Dominic Johnson (@kongoecho) and Simone Schlindwein (@schlindweinsim) of Germany’s Tageszeitung.

P.s.: This post does not suggest that military options are the only and best way to neutralize the FDLR. Elsewhere I have argued for a multi-thronged approach, involving means other than military ones (here and here).

The Life and Death of General Bahuma

After rumors circulated on Saturday evening, the Congolese Defense Minister confirmed today that General Lucien Bahuma Ambamba passed away last night in a hospital in Pretoria, South Africa. He reportedly died of a cerebrovascular accident after falling ill on Thursday night in Kasese, Uganda, where he met his Ugandan counterparts to evaluate ongoing military operations against the ADF rebel group in Congo. Bahuma’s death is a major blow to the leadership of the army.

During his last function as commander of the 8th military region in North Kivu, Bahuma led the army into battles against the M23 and ADF rebel groups. According to photo journalist Pete Muller who covered the conflict extensively, “General Bahuma was as fine an officer as I’ve ever encountered and was a critical player in the FARDC’s victory against M-23 rebels last fall (see also Pete’s video dispatch).” Other observers say that he was a respected and progressive soldier who helped reorganize the army in the east. Tellingly, he has never been singled out by the United Nations Group of Experts for misconduct. An independent military expert said s/he has never heard anything negative about him.

The Congolese Defense Minister described Bahuma as “a man absolutely devoted, a brave officer, someone who put his heart and soul to his mission,” while civil society representatives in Beni called him the “pride” of the army and the “liberator” of the territory. Condolences came also from the Congolese Prime Minister, the Governor of North Kivu, and the Chief of MONUSCO.

His passing comes eight months after the assassination of Colonel Mamadou Ndala (video here). While the circumstances of death are different, some see parallels between the two incidents, provoking suspicions that his death was not natural but the result of poisoning. Fighting the M23, Mamadou and Bahuma won the hearts and minds of many Congolese and the deep respect of their fellow soldiers whom they regularly accompanied to the front (video here). Jeune Afrique calls Bahuma a “homme de terrain.”

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, an expert on the army said the “army in North Kivu is very shocked. The two heros fighting M23 have disappeared at a time when there are rumors that ex-M23 elements are remerging. […] It will be difficult to convince them that he [Bahuma] died of a natural death. There will be a trauma inside the army.” The newspaper La Prospérité said the “news had the effect of a bomb.”

If true, this could weaken an army which soon may have to engage one of the most complex armed groups remaining in eastern Congo, the FDLR. In addition, civil society in Beni is afraid that his loss might negatively affect ongoing operations against ADF.

All the while in Goma, the news about the General’s death have already sparked an improvised demonstration of female military dependents on Sunday, followed by demonstrations of students in Goma and wives of soldiers in Beni on Monday. In response, the Governor of North Kivu Julien Paluku and the civil society in Beni territory called on the population to remain calm and police deployed to strategic points in Beni town.

While one should avoid hasty speculations and await the autopsy promised by the spokesperson of the Congolese government, it is important to bear in mind that the government has yet to deliver the results of its investigations into the killing of Mamadou. It is therefore important that the South African authorities provide for a transparent and swift examination, free of political interference. (See similar demands by the Congolese civil society organization LUCHA and North Kivu’s civil society).

The next few days and weeks will also bring a few reshuffles in the army. According to some MONUSCO officials, General Lembo will replace Bahuma, whose former boss General Amisi, who has recently been cleared of serious charges of leaking weapons to rebels, might be reinstalled, too. This, however, would be a “catastrophe,” according to an expert on the army.

The Life of General Bahuma

Born on 26 June 1957 in Yangambi in Orientale Province, General Bahuma has a long track-record in the Congolese army. Bahuma underwent military training at the officer school in Kananga, Kasaï-Occidental (later in France, too) before he served with the Special Presidential Division of former dictator Joseph Mobuto. Later he became the commander of the Training Center for the Pambwa Commando in North-Ubangi, Equateur Province. He was then appointed commander in the military wing of the Movement of the Liberation of Congo (MLC) of Jean-Pierre Bemba, who stands accused of several counts of crimes against humanity and war crimes in front of the International Criminal Court. After serving as commander of the 5th military regiment in Bas-Congo, he replaced General Mayala as commander of the 8th regiment in North Kivu in July 2012.

- If you want to get a feeling of how Congolese are reacting to the news, consider joining the Facebook group Parlons-En!, follow Congolese journalists on Twitter and listen to Congolese radio stations online.

- International coverage from RFI (here, here and here), Jeune Afrique (here and here), BBC, Associated Press.

- Congolese reporting on Radio Okapi (here, here, and here), Le Congolais, L’Avenir, ACP, La Prospérité, and Le Potentiel. Here’s also an overview of reactions by Congolese media on Monday, 1 September.

- For pictures of General Bahuma, Colonel Mamadou and the latest M23 crisis, see photography by Pete Muller (@pkmuller), Phil Moore (@fil), Daniel McCabe and Simone Schlindwein (@schlindweinsim).

- For detailed accounts of Bahuma’s and Mamadou’s fight against the M23 and ADF, see here and here.

Photo credits: Pete Muller (photos 1,2) and Phil Moore (photos 3-12).

US – Africa Summit starting today

Today, African heads of states will gather in Washington D.C. to expand and widen interstate relationships through investment, trade, security, human rights, and democracy. Let’s get you up to speed:

- Check out the official website of the Summit detailing the program of events, side events, national statements and much more. Inter Action provides for another very comprehensive list of all side events at the Summit.

- The Council for Foreign Relations gives a neat overview of “What to expect of the US-Africa summit.” So does Reuters in its article ‘Late to the Party, Obama Seeks Bigger U.S. Africa Role.’

- National Security Advisor Susan Rice drew attention to Africa’s progress in the past two decades and its possibilities for economic growth, good governance and long-term stability, in a speech at the U.S. Institute of Peace on 30 July. Later, the Project Syndicate took a critical stance, considering the basis – and the limits – of the continent’s progress.

- In a short article published in late July, the Brookings Institute argues to pay particular attention on Congo during the Summit.

- Foreign Policy’s Jeffrey Smith asserted that the Summit “ will only succeed if the White House eschews autocrats in favor of a new generation of democratic champions.”

- Earlier, Gordon asked whether the Summit might actually do more harm than good.

- Also in Foreign Policy, Elias Croll proclaimed that the latest Ebola outbreak will unlikely feature heavily at the Summit.

Four years ago today: The Luvungi rapes began

Four years ago today, elements of Mai Mai Sheka, FDLR and army deserters started to go on a rampage along the Kibua to Mpofi road in Walikale territory (map). Over the span of just four days, they reportedly raped 387 civilians – 300 women, 23 men, 55 girls and 9 boys. According to a perpetrator handed over to the Congolese army and interviewed by the United Nations Group of Experts, Sheka himself ordered the rapes in order to garner public attention.

“I felt personally guilty and guilty toward the people I met there,” said Atul Khare, the UN Assistant Secretary General for Peacekeeping, who visited Luvungi. “They told me, ‘We’ve been raped, we’ve been brutalized, give us peace and security.’ Unfortunately, I said, that is something I cannot promise.”

Arrest attempts

Despite an arrest warrant issued on 6 January 2011,* Sheka himself enjoys near total impunity. In July 2011, Sheka had visited Goma for medical treatment and escaped an attempt arrest by the Congolese authorities and MONUSCO. Human Rights Watch reported that he was “allegedly tipped off by Congolese army personnel who had a close working relationship with him.” Later in the fall of 2011, Sheka was so bold as to run for National Deputy as well as the re-election of President Kabila. In a video interview with Al Jazeera, Sheka said “If I am guilty of all of these [rape] crimes, why then are all these people here to support me? […]. Just you try it [arrest me] and these crowds will beat you,” he said. Sheka did not win the elections, however.

Two and a half years later, in April 2014, Sheka mocked the authorities once again, when the North Kivu Governor together with his police chief and the head of MONUSCO in North Kivu met Sheka at his former headquarters in Bunyampuli. Below is a two-minute video of the visit.

In an informal interview, a UN staff said that “[t]he team flew to Walikale to sensitize the community not to talk to Sheka. They never meant to meet him. They knew he was around but they never expected him to come. But then Sheka stormed into the village, calling on them to bring development to Walikale. He even fell down on his knees.”

Despite the presence of arguably the three most important figure heads in North Kivu and accompanying security forces, Sheka walked away once again. Admittedly, any arrest attempt would have been too risky. Sheka was accompanied by armed men and the village was full of civilians. Nonetheless, the incident was mind-boggling: How can it be possible that authorities have not been able to arrest a rebel leader known for abhorrent human rights violations and designated by the United Nations for targeted sanctions?

In speaking to several high-ranking officials of the peacekeeping mission, it is evident that they are very keen on bringing Sheka to justice. In an interview in May 2014, Force Commander General Dos Santos Cruz said that “Sheka is a criminal. We must get him.” Earlier in October 2013, Martin Kobler, the Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in the DRC, shared such sentiment: “These atrocities [by Sheka] are unimaginable and are contradicting the values of humanity. This must have consequences. There cannot be impunity for such atrocious acts.”

But MONUSCO is constrained by political realities. During an informal meeting a senior MONUSCO official admitted that “legally speaking, we can arrest Sheka unilaterally but politically speaking, this is impossible. We need the OK from the Congolese government.”

What is Kinshasa waiting for?

For three times now, the Congolese government has tried halfheartedly to arrest him but to no avail. On the political front, the Government of Congo has tried to negotiate with Sheka repeatedly; attempts that have been fruitless at best. As early as 2011, Sheka negotiated with the Government of Congo about a possible integration into the army. (See his list of demands here). Two years later, on 6 November Sheka sent another list of demands to the Government, incl. amnesty and integration into the army or police for all his elements with the recognition of all (self-proclaimed) ranks. Sheka’s claims are ludicrous and should rightly be rejected.

Militarily, FARDC with the support of MONUSCO launched operations against Sheka on 2 July on the axes Walikale-Kibua (Ihanda), Kashebere-Kibua (Luberiki) and Kashebere-Walikale. By 10 July, 20,000 residents had fled the fighting. On the same day, MONUSCO reported that the army had secured the locality of Kibua (47 km east off Murongo) and Sheka’s headquarters at Bunyampuli. On 28 July, MONUSCO’s military spokesperson confirmed that “[t]he Congolese forces are controlling all the [areas] of Hihama and Utunda plus the mining area of Angoa, which was some kind of stronghold for Mai Mai Cheka elements.”

Conclusion

While Sheka has been dislodged from some of his areas, he remains at large. Above all, arresting Sheka does not require so much a military action but a political process. Sheka remains at liberty because among other factors he is protected by very powerful elites in politics, the military and business who have and continue to benefit from his racketeering. At the same time, protecting Sheka ensures their own protection from prosecution.

Arresting Sheka should not be too complicated an endeavor provided Congolese authorities finally sever these ties and are willing to bring him to justice, honoring the 387 survivors that fell victim to gross human rights violations starting today four years ago.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Background: Who is Sheka?

Mai Mai Cheka – also called Nduma Defence of Congo, or NDC – is led by 38-year old “Gen.” Ntabo Ntambui Cheka, an ethnic Nyanga from Walikale territory. In late 2010, the United Nations Group of Experts concluded that NDC had been “generated by criminal networks within FARDC that compete for control over mineral-rich areas.” The experts argue that the 85th brigade of the Congolese army led by Colonel Sammy Matumo used Sheka to prevent its rival the 212th brigade to take control of the Bisie cassiterite mine in Walikale. At that time, the 212th brigade was made up of former CNDP rebels who were awarded control over Bisie to reciprocate them for their earlier integration into the army.

Prior to becoming a rebel leader, Sheka worked for the miners cooperative COMIMPA (Coopérative minière de Mpama Bisie), and then with the mining company Mineral Processing Congo, which holds the exploration rights to the Bisie mine. He has had no prior military experience.

Objectives

Sheka’s official objectives have changed over time. Initially, he meant to prevent Congolese refugees in Rwanda from returning to Walikale. Later, he claimed to free mines in Walikale from the interference of the army. Then in 2013, a former NDC soldier and NDC cadres told the Group of Experts that Ntaberi’s main objective is to fight against the FDLR, which used to be Sheka’s closest ally (see more below).

In a seeming contradiction, Sheka has extensively exploited natural resources in Walikale territory, especially gold and tin, and attacked key mining sites at Bisie, Mubi, Njingala, Kilambo and Omate. As a case in point, in late 2011, the Group of Experts reported that “NDC controls more than 30 remote gold mines throughout Ihana and Utunda groupements north of the Goma-Walikale axis, where diggers work and produce gold directly for the groups. NDC also imposes an additional production tax of either 10 per cent of output or a fixed amount of gold per an allotted period of time.” Next to gold and tin, Sheka also controlled a number of diamond-mining locations in 2011. In mid-2013, the Group of Experts reported that Sheka is benefiting from taxes on almost one hundred mining sites in Walikale.”

Friends

Sheka has enjoyed good relationships to elements of the Congolese army. As the Group of Experts reported in 2010, Sheka has been supported amongst others by the former Deputy Commander of the 8th military region Colonel Etienne Bindu. In 2011, the Group concluded that Bindu played “an instrumental role in the creation of NDC” and remained a “critical supporter.” In addition, the Group heard of indirect support given to Sheka by Colonel Yusuf Mboneza, then the FARDC 212th brigade commander. In 2011, Sheka reportedly collaborated with Colonel Abiti Albert, who reports directly to General Amisi, then the Commander of FARDC. Moreover, the FARDC battalion Commander at Mubi in the 805th regiment Lieutenant Colonel Nyongo, his colleague Captain Zidane, and the Deputy Sector Commander for Walikale Colonel Ibra were also identified as sympathetic to Sheka.

Next to the army, NDC has received critical support from armed groups, including the FDLR before they fell out and become fierce enemies. The FDLR faction Montanta led by Captain Seraphin Lionso and overseen by Lieutenant Colonel Evariste “Sadiki” Kanzeguhera reportedly assisted NDC in 2010. Other notable FDLR commanders who aided Sheka include Sergeant Major Lionso Karangwa and commander Omega. However, in November 2011, Sheka killed his former ally Sadiki, ending the alliance altogether.

Sheka also received assistance from ex-CNDP elements such as commander Emmanuel Nsengiyumva, who deserted his FARDC post as the commander of the 2,111th battalion in December 2009. In mid-2011, Sheka had allied with ex-CNDP General Bosco Ntaganda. In late 2013, the Group of Experts reported that “NDC had allied with M23 until the March 2013 division of the movement, after which the ties weakened,” adding that NDC had also sided with elements of Raia Mutomboki from Walikale.

As for third-country support, Rwandan government officials have allegedly supported Sheka in carrying out the attack against Sadiki. A NDC deserter informed the Group of Experts that during the M23 rebellion, Sheka “received telephone calls from […] senior Rwandan officials on a daily basis.”

As with regards to support by business elites, the Group obtained “significant evidence” in 2011 that the mining company Geminaco was in bed with Sheka, sharing profits and seeking the rebels’ help to take out a competitor. On the political side, as per one account, the former administrator of Walikale territory Dieudonné Tshishiku Mutoke was among the clandestine supporters of Sheka in 2011. Nyanga politician Willy Mishiki (UHANA) is another perceived ally. Lastly, NDC received extensive assistance from his relatives, including his uncle Bosco Katenda, the group’s spokesperson, his younger brother Soki Ntaberi, his two wives Francine and Celine as well as his cousin Jerome Katenda.

Enemies

Next to the FDLR, Sheka’s archenemy is the APCLS, a majority Hunde armed group in parts of Masisi territory. On the side of the army, key enemies included Col. Chuma and 803rd regiment Commander Col. Pilipili Kamatimba, who were killed in spring 2012.

Further readings:

The United Nations Group of Experts provide the best and most comprehensive public account on Sheka. Follow the links below and look up the respective paragraphs to learn more about NDC.

S/2009/603, paras. 220;

S/2010/596, paras.34-43, 203 and box 4;

S/2011/345, paras. 33-45;

S/2011/738, paras.190-218, 432, 433, 448-453, annex 42-51;

S/2012/348, paras. 60-63, 93-95, annex 2,3;

S/2012/348/Add.1, paras. 36, 52;

S/2013/433, para. 167; and

S/2014/42, paras. 42-46

For a detailed report of the Luvungi rapes, see the comprehensive report of the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office as well as the account of the Group of Experts (esp. paras. 144-6), a feature by New York Times, and Laura Heaton’s Foreign Policy article “What happened in Luvungi?”

* Apart from Sheka, authorities have unsealed seven other arrest warrants for crimes against humanity committed at Luvungi and surroundings against Sheka’s Chief of Staff Sadoke Kikunda Mayele, FDLR’s Captain Seraphin Lionso and another FDLR commander, in addition to four deserters from the army. From these seven, only two have been arrested. Mayele had been handed over on 5 October 2011 by Sheka but later died under mysterious circumstances in the prison of Goma. An interviewee told me that s/he was threatened when inquiring into the death of Mayele, who allegedly died of an illness. Another suspect escaped from prison in November 2012.

The Death of Rebel Leader Paul Sadala – Questions Remain

In its latest report released on 25 June 2014, the United Nations Group of Experts revealed new information on the death of Paul Sadala, former leader of Mai-Mai Morgan.

Following earlier negotiations about his surrender, Morgan allegedly agreed to meet the army in person in Badengaido with some 40 of his men to discuss his terms of surrender (see letter below). One of Sadala’s desires was to become General of the Congolese army. Together with some of his men, he then traveled east-bound to Molokay, where he met General Fall. According to Fall’s account, after an initial conversation, Morgan refused to travel onward and intended to return to the bush with his men, six of whom were reportedly armed. Gen. Fall then ordered his men to shoot Morgan once in each leg. During the ensuing shootout, a number of soldiers and rebels were either killed or injured. The army proceeded to drive Morgan to the MONUSCO base at Komanda, where they arrived three and a half hours later. All the while, Morgan reportedly “received minimal first aid” and was “barely alive on arrival,” dying shortly thereafter. For a detailed reconstruction of the events, see photos below.

In conclusion, the Group “believes that a flawed plan to extract Morgan from the bush resulted in a disproportionate use of force during Morgan’s arrest, ill-treatment during his transfer and negligence in treating his wounds.” This conclusion is “based on analysis by the Group of photographic and video evidence, in addition to interviews with FARDC and MONUSCO officials.”

While I do not call into question the Group’s conclusion, I would like to stress that only FARDC elements actually provided a first-hand account of the shootout (no MONUSCO staff was present during the pivotal moment). Given the army’s involvement, their take on the events should be treated with a certain measure of skepticism. For instance, it still remains unclear why Morgan was “bleeding profusely” from a wound on his left hip, a fact that General Fall could not explain nor could the Group identify its cause. In addition, it would be helpful to know what the Group thinks of the finding that Morgan had been tortured by a sharp object, as reported by Radio Okapi on 20 May. I am also curious to know which entity provided the photographic and video evidence.

In line with my earlier reporting below, I share the Group’s assessment that the death discourages elements from Morgan and other groups to come out, prevents the release of kidnapped women and children, and might harm the ongoing disarmament, demobilization and reintegration process in Ituri. The Group goes as far as arguing that it might have implications for the “long-term security and stability in the Ituri Mambasa territory.”

All the while, it remains to be seen what the consequences for the “flawed plan, “ill-treatment” and “negligence” are going to be.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Reconstruction of events by the UN Group of Experts:

Pic 1: Morgan (black shirt and dark blue jeans) meets Gen. Fall (standing on the right, wearing FARDC military uniform, with red insignia on the shoulder) at Molokay.

Pic 2: An unarmed Morgan and Gen. Fall get into Gen. Fall’s car for private discussion, surrounded by FARDC soldiers.

Pic 3: Morgan in Mambasa, approximately 2 hours post shooting. Morgan is seated with other wounded persons in the back of a pickup-truck, wearing black shirt and underpants.

Pic 4: Crowd gathers in front of the Mambasa health facility (Centre de depistage SIDA) where some wounded are dropped off. Morgan is not treated here and continues the journey at the back of the truck.

Pic 5: 14h54: Gen. Fall at the entrance of MONUSCO camp in Komanda.

Pic 6: 15h05: Picture taken ten minutes post arrival in Komanda. Morgan is barely alive and appears to have moved his arms.

Pic 7: 15h05: MONUSCO provides medical assistance in Komanda.

Pic 8: 16h01: FARDC and MONUSCO soldiers transport Morgan transported on a stretcher. A MONUSCO soldier holds a drip, and bandages are apparent on Morgan’s leg and hip.

Pic 9: 16h01: The MONUSCO helicopter is visible, which brought an Air Medical Evacuation Team (AMET) to Komanda.

Pic 10: 16h07: Morgan on the ground near the helicopter.

Pic 11: A medical officer from the AMET tries to resuscitate Morgan

Pic 12: Resuscitation attempt continues.

Pic 13: The AMET continues resuscitation attempt.

Pic 14: 16h48: Morgan is in the helicopter.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Letter to President Kabila from Morgan

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Headquarters General Mumbiri

Mai Mai Lumumba Simba

Declaration of General Morgan to His Excellency Rais Joseph Kabila Kabange

I heard your testimony about the blood of us Congolese which is spilled every day. I was happy when I learned that small rebel groups like ours would no longer be arrested or killed. Head of State, you are our father and we come at your feet to listen to your voice Ah! Why do we kill each other, it gave me the desire to leave (the forest) and find out the truth. I come, knowing it is false — but if it was true J. Pierre Bemba would be freed already, Toma Lubanga and all the others are still there. My request to my father is this one:

1) Confirm my grade of general

2) Give us military uniforms

3) Supply us with all sorts of weapons

And to show that I am your son and that I am ready, send me everywhere your enemy is.

After having sent you my request…

——————————————————————————————————————————

New developments in the death of Paul Sadala, former leader of Mai Mai Morgan: He was tortured

Following the launch of an investigation by the Congolese military into the suspicious death of rebel leader Paul Sadala on 14 April 2014, it was reported on 20 May that FARDC soldiers had tortured Sadala prior to his death. While the findings are interesting and revealing, it begs a lot of questions. In the following, I want to outline the many questions that remain unanswered. While I don’t have many of the answers myself yet, I hope it shows the continuous controversy and keeps the debate ongoing.

THE ACT OF TORTURE

Why was he tortured? Was torture used to force him to reveal information? If so, what information? I do not want to conspire but Sadala did have vital intelligence on the FARDC: According to findings of the UN Group of Experts, Mai Mai Morgan enjoyed “close relationships” with senior leaders in the FARDC ninth military region, including Maj. Gen. Jean Claude Kifwa, who provides logistical support, arms and ammunition.

If he simply had to be silenced, why not kill him without torturing him first? Alternatively, was the torture simply used to punish and humiliate him?

Who tortured him? Who gave the orders versus who committed the direct acts? Major Enock Kinzambi, commander of the FARDC battalion in Mambasa, Orientale Province, was the first to be arrested on 29 April. Radio France International reported he was arrested because he had lied that Morgan had been disarmed. But did he also torture him?

Was it an act of an individual army element or an act commissioned by a higher authority?

What was the role of the high command? And where were they, especially General Fall Sikabwe to whom Sadala reportedly surrendered to? Did Sikabwe and the high command fail to prevent the torture?

SADALA’S EVENTUAL DEATH AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH

What was the cause of his death? Did Sadala die of the consequences of torture? (He reportedly had “profound wounds” (incl. at his tibia) inflicted by a sharp object.) Or did he die in the later shootout as alleged by the army? If the shootout really happened, what started it?

Why did the army agree to surrender Sadala’s tortured body to MONUSCO? Did they resist giving up the body? Were they afraid that MONUSCO would find out about the torture? Or, on the contrary, did they want MONUSCO to find out? If that’s the case, are there two different sides, one that tortured and the other one that wanted to help reveal it? Or did the elements that surrendered Sadala’s body not know about it?

Why did MONUSCO take him when he was already dead upon arrival? For the purpose of an investigation? To recap, the first official account of the government falsely reported that Morgan was bleeding to death when he was being flown out by a helicopter of MONUSCO. The UN, however, denied this, clarifying that he had already been dead prior to arrival. “We only received the remains of Paul Sadala from the DRC army. He was already dead”, Charles Antoine Bambara, the UN mission’s public information officer, told reporters.

Did any members of Sadala’s family or kin come forward to claim the body for burial?

THE INVESTIGATION

MONUSCO

When MONUSCO transported his corpse did they inspect his body and find anything?

Did MONUSCO’s team of investigators deployed later see the body and notice the signs of torture? If so, did they inspect it before the army inspector saw the dead body?

How long did MONUSCO hold on to the corpse before returning it to the army? What did they do with it in the meantime?

What’s the status of MONUSCO’s investigation? What is their stated objective in carrying out the investigation?

FARDC:

At times, military prosecutors vulnerable to political and outside interference were prevented from implicating elements of the army in such terrible a crime. They had to cover it up. So, what explains the prosecutor Gen. Major Mukuntu Kiala’s conduct in this case? I can think of several possibilities, including:

- the act was an uncoordinated act by an individual who does not enjoy protection from higher authorities/elites.

- the military prosecutor had free reign to conduct his investigation and present his findings.

- MONUSCO knew about it after transporting him and pressured the Congolese army behind closed doors to reveal the truth. This scenario strikes me as the most convincing.

By whom and where was he buried? I imagine he was buried for reasons of contamination.

Who called for the exhumation and later autopsy? Who exhumed the body and who conducted the autopsy?

Did the prosecutor Gen. Major Mukuntu Kiala gather any evidence other than the autopsy results, such as witness testimonies?

NEXT STEPS

Have there been any new findings?

What are going to be the consequences of the findings we now know about? Have there been any new arrest warrants or temporary suspensions? I have not heard of any yet.

What has happened to the 42 other elements that have been captured? Where are they? Are they dead?

Is Sadala’s death going to deter other rebel leaders from surrendering? What incentives and guarantees must be provided to encourage other rebel elements to surrender? What will be the plan to communicate the results of the investigations to ensure that combatants are sent a message that any foul play by the army was an isolated and intolerable incident?

Where is the rest of the group and what are they doing?

- On 11 June, MONUSCO reported that FARDC continues to fight elements of the group active in the territory of Mambasa. On 3 June, the army allegedly arrested two Simba elements in Bafwakoa, located 39 km east of Nia-Nia. They were transferred to Kisangani. The elements carried two AK-47s.

- On 21 May, MONUSCO said 20 elements supposedly belonging to Morgan attacked a village 33 kilometers east of Nia-Nia, pillaging five shops, stealing one motorbike, and kidnapping two men and two women. The Congolese army reportedly deployed its men to the region, wounding one.

- Two days prior to the attack, on 19 May, MONUSCO deployed one operational post in Nia-Nia, charged to protect MONUSCO, prevent attacks at civilians and conduct “robust patrols.”

- On 14 May, MONUSCO revealed that elements of Sadala had attacked on 8 May positions of the Congolese army in the gold site of Mutshatsha, 300 kilometers west of Bunia. Two rebels and one soldier reportedly died. The confrontations later led to the displacement of people towards Bandegaido et Nyanya.

- Two days prior, on 12 May, a group of Morgan elements, on behalf of Manu, attacked the village of Bakutambili, located 33 kilomters east of Nia-Nia, pillaging shops and markets. They also reportedly closed all schools and forcibly sent the pupils home. The rebels later withdrew in the face of the arrival of the army.

- On 9 May, Morgan rebels allegedly attacked the army in Orientale Province (Muchacha, Bandegaido, Mambasa). They are said to have killed one soldier, wounding three others.

Does the group actually still exist as such or are the activities described above now the results of splinter groups that seek survival?

Did anyone – and if so who – replace Paul Sadala? On 7 May, MONUSCO alleged that Sadala’s young brother Mr. Mangaribi was officially appointed as General and replacement of Sadala. The ceremony is said to have taken place in the village of Bandumbisa, located 47 km off Nia-Nia.

What happened to Sadala’s notable colleagues lieutenant Manu and/or Jean Pierre aka JP or Docteur?

What’s the status of the war crimes trial against 24 Mai Mai Morgan elements that started on 1 March?

CONCLUSION

As stated earlier, unfortunately, I don’t have the answers to many of these questions yet. We might never find them. But I believe identifying outstanding questions is a first and necessary step.

——————

New developments in the death of Paul Sadala (update as of 2 May 2014):

Following the launch of an investigation into Morgan’s death by the Congolese military, authorities reportedly arrested FARDC Major Enock Kinzambi, commander of the FARDC battalion in Mambasa, Orientale Province, on 29 April. He’s the first suspect in custody. (MONUSCO has deployed its own investigate team. Findings are forthcoming). Radio France International reports he was arrested because he had lied that Morgan had been disarmed.

Earlier on 25 April, France 24 and Sonia Rolley of RFI received an exclusive video that shows Sadala in FARDC custody. The video underscores the opacity of Sadala’s death. Sonia continues to report frequently on the issue so make sure to add her to your Twitter feed (@soniarolley). Also follow Christophe Rigaud (@afrikarabia), who published an interesting blog post on Sadala on 24 April.

Also on 24 April, MONUSCO reports that elements supposedly belonging to Mai Mai Morgan raped six women, wounded ten men with gun shots, and stole several goods in an attack on the mining site of Kakolo, 90 km southwest of Mambasa-centre (map). Several teenagers have been allegedly kidnapped to transport the loot. As a response to this, MONUSCO says it has established on operational post in Epulu, 70 km west of Mambasa as part of its operation Eagle Claw meant to secure the Epulu-Molokai-Badengaido axis (map). A day prior, on 23 April, four Morgan rebels supposedly surrendered to the army in Cantine, 54 km southwest of Beni, MONUSCO says.

P.s.: According to the latest information, Sadala surrendered to General Fall Sikabwe.

Situation as of 23 April 2014:

Paul Sadala aka Morgan was killed on 14 April 2014 after he surrendered with 42 of his men to the army two days prior in the locality of Bandegaido, Mambasa territory, Orientale province (map). It is still unclear why Sadala surrendered in the first place. One possibility might be that he wanted to benefit from a new disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration program recently put in place.

According to the account of the government (here and here), Morgan and his men were transferred from Molokaï village to Bunia town, the capital of Ituri district, Orientale Province. “When we reached the town of Mambasa which is about 100 km south of Bunia, Morgan refused to continue his way to Bunia unless he was given the rank of general. During the standoff, he was injured on his legs”, army chief Gen Felix Sikabwe said. The government reports that four of his men (Reuters reported two) and two soldiers were also killed.

The first official account of the government falsely reported that Morgan was bleeding to death when he was being flown out by a helicopter of the peacekeeping mission MONUSCO. The UN, however, denied this, clarifying that he had already been dead prior to their arrival. “We only received the remains of Paul Sadala from the DRC army. He was already dead”, Charles Antoine Bambara, the UN mission’s public information officer, told reporters.

The accounts of Sadala’s death are competing, sparking some to question it altogether. Two days after his death, the provincial deputy and member of the presidential majority Joseph Ndiya accused the Congolese army assassinated Sadala in order to silence him (possibly for his reported involvement with elements of the army – see below). The spokesperson of the Congolese government, however, expressed his regret that Morgan could no longer be brought to justice for charges issued on November 2012 for war crimes and crimes of sexual violence. Since 1 March, 24 of his men stand trial for war crimes.

MONUSCO announced that it would launch its own investigations into the killing and probe into the whereabouts of the remaining 42 men. As of 14 April, MONUSCO did not know whether they were still alive. The mission is well-advised to conduct a rigorous assessment and report on its findings in due time. As a UN official told Reuters: “There is a worry that other warlords will not come forward to surrender because it is unclear what happened to Morgan.” The leader of the civil society of Ituri district echoed this sentiment, arguing that the killing complicates the surrender of Morgan’s fellow members that are still at large. As if to underscore his remarks, remaining elements of Mai Mai Morgan reportedly staged two new attacks on 15 and 16 April, causing women and children to flee. Days later, on 18 April, Mai Mai Morgan rebels attacked two villages situated close to Salate in Mambasa territory, MONUSCO said. They reportedly pillaged gold, raped four women and kidnapped a number of men.

Who’s Mai Mai Morgan?

A native of the Bombo community, Sadala has been the overall commander of the group. Other leaders include his lieutenant Manu and Jean Pierre aka JP or Docteur. In August 2013, together with my colleague Fidel Bafilemba I estimated that Morgan had around 250 men at his disposal, mostly from the ethnic groups Nande, Ndaka, Bakumu, Bapiri, and some FARDC deserters. (Note that the UN Group of Experts in mid-July 2013 only spoke of “several dozen” men.)

The group has enjoyed friendly relationships with Mai Mai Simba and the Union for the Rehabilitation of Democracy in Congo, or URDC (for more information on the latter two, see here). According to findings of the UN Group of Experts, Mai Mai Morgan enjoys “close relationships” with senior leaders in the FARDC ninth military region, including Maj. Gen. Jean Claude Kifwa, who provides logistical support, arms and ammunition. The group is operating in Mambasa and Bafwasende districts in Orientale Province (see mapping by Christoph Vogel).

While Morgan has no official objective, the group has been heavily involved in the illicit exploitation of natural resources. In its final report for 2013, the UN Group of Experts reported that during 2013 Morgan shifted his focus away from poaching elephants in the Okapi Fauna Reserve in Haut Uélé and Ituri districts of Orientale Province to attacking gold mines.

Reported gross human rights violations committed by Mai Mai Morgan include pillage, kidnapping, rape, including sexual slavery, and cannibalism. In mid-2013, for example, the UN Group of Experts reported that from 1 to 5 November 2012, the group raped or sexually mutilated more than 150 women during a series of attacks on villages in a gold-mining area south of Mambasa.

Future

The death of Morgan and capture of 42 men is a serious – possibly fatal – blow to the group. It remains to be seen whether his successors Manu and Jean Pierre can revive the group. Whatever the future will bring for Mai Mai Morgan, the situation in southern Orientale Province will remain volatile for the nearby future, however. Other rebel groups such as ADF and FRPI – albeit weakened in light of recent FARDC operations- continue their activities. Meanwhile, the near absence of any effective policing in Ituri “is fuelling mob violence which has seen about 100 people killed and 1,500 houses torched in the past year, according to local civil society groups,” IRIN News reports.

Further reading:

- The most detailed and authoritative accounts of Mai Mai Morgan can be found in the bi-annual reports of the UN Group of Experts, including S/2014/42 (23 January 2014, para. 64-67); S/2013/433 (19 July 2013, para. 72-78); and S/2012/843 (15 November 2012, paras. 128-132).

- MONUSCO provides a neat overview of commentary by Congolese media a day after Morgan’s death.

- Enough Project’s August 2013 overview (p.10) of Mai Mai Morgan.

- On 23 January 2013, IRIN News reported on the activities of Mai Mai Morgan.

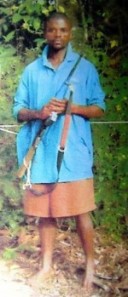

P.s.: The picture is from the UN Group of Experts S/2013/433 (19 July 2013; annex 46, p.116).

Congo: What’s happening in FDLR’s stronghold in Rutshuru?

By Timo Mueller

Editor’s note: Master student at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs Priyanka Johnson edited the post.

The northern territory of Rutshuru, in the North Kivu province of Eastern DRC, has for a long time now been one the strongholds of different factions of the FDLR (maps here and here). Drawing from the knowledge gained by a series of field visits in the latter half of June this year, in and around the administrative entity of Binza, certain identifiable trends in security dynamics are noteworthy.

The most dominant armed group in the area of Nyamilima-Katwiguru is the FDLR, which consists of three factions, namely FOCA, FPP and RUD. They reportedly operate in the north, southwest and east of Nyamilima respectively. Many elements of these FDLR factions do not live in camps but are embedded within local communities. Although they are led by notable experienced FDLR commanders, the factions in the area are reportedly not as well-structured as their counterparts in Walikale, Masisi or Lubero territories (North Kivu province).

Other groups active in the area include remnants of the groups Maï-Maï Shetani and Nyatura-MPA. However, a majority of both these groups surrendered en masse in late 2013 and early 2014 following the defeat of the M23 rebel group. Shetani remnants – estimated to be around 50 elements – allegedly support the Congolese army in altercations with the FDLR, while many elements of Nyatura-MPA are said to have joined FDLR/FPP, a faction reportedly led by successors of FDLR/Kasongo. All three FDLR factions and Nyatura-MPA recruit mostly Hutu, while Maï-Maï Shetani largely relies on youth from the Nande ethnic group. In Masisi and Rutshuru territories, Hutu constitute the majority, while in the province at large it is Nande that make up the majority.

The nearby Virunga National Park provides the groups with a range of lucrative resources such as timber, charcoal and wildlife. The park’s landscape also offers sanctuary from adversaries.

FDLR

The area has been dominated by the FDLR for a long time, even during the M23 rebellion from April 2012 until November 2013. As a successor to FLDR-SOKI and FDLR-KASONGO, FPP is the most dominant group in the area. Interestingly, many stakeholders called FPP a “false FDLR,” despite it being the biggest faction. The purported reason for this is that FPP reportedly heavily relies on Congolese Hutu youth and elements of Nyatura-MPA. As one interviewee alleged, “Of 50 FDLR-FPP elements, only 5 are Rwandans.” Another stakeholder estimated the proportion of Congolese youth inside FPP to be as high as 95%. While this is very likely an exaggeration it gives a sense of the group’s public perception as “false FDLR.”

The information below spells out reported current positions of FPP with an approximate number of elements. While efforts have been made to corroborate the information to the extent possible, the data is based on the perception of the interviewees and even then, serves as a snap shot in the time frame of late June. This is both due to the mobility and continuing DDR process resulting in reduction of the strength of the groups. Further, the names of many leaders are most likely aliases.

- Katwiguru/ChezMaheshe

- Capt. Senga + asst. Lt. Niyo (both are Congolese).

- 20 elements.

- Muzinga

- Capt. Rupfu (Rwandan) + asst. Lt. Elia (Congolese).

- 10 elements.

- Mbugani (19kmoffKiwanja,Rubeguro)

- Capt. Assumani (Rwandan) + asst. Lt. Yakobo (Congolese).

- 10 elements.

- Kigaligali (Headquarters). Note that others said that FPP’s HQwouldbeinKatwiguru.

- Col. Dan, Capt. Bolingo, Adj.Gashubi, Adj. Alex, Yabiso, Claude, Maj. Ntabwaba, Capt. Odeyi (all Rwandan).

- 30 elements.

- Karabuge (8km off Buganza)

- Col. Mateso, Lt. Col. Kambale (both Rwandan).

- 80 elements.

- Kilima-Nyuki (nexttoKarabuge).

- Lt. Col. Kambale.

- 15 elements.

- Kasoso (+/-8kmsouthwestoffBuganza).

- Maj. Kadaffi, Adj. Capt. Eric.

- 25 elements.

- Bisoso (8kmwestofNyamilima where MONUSCO’s COB is. The Congolese army has a position justtwokilometersoffBisoso).

- Capt. Bernard, Lt. Yusufu.

- 10 elements

FOCA

Main strongholds of FOCA reportedly include Kasave, Kikito, Kabuga, and Nyabanira, which are near Katwiguru. One informant estimated FOCA to have around 200 men.

FDLR’s relationship to the Congolese army (FARDC):

According to several interviewees, the FDLR currently does not enjoy an amicable relationship with the 107th regiment of the Congolese army led by Col. Blaise. “FARDC no longer cohabits with FDLR. They became enemies,” one stakeholder declared. This was corroborated by two observers, who stated “There is no relationship” and “FARDC does fight FDLR properly.” The army has been attacking FDLR in early and mid-June 2014 around Katwiguru. According to one testament, the army managed to disrupt FDLR’s fishing practices in the area and caused loss in FDLR’s communication equipment. The interviewee added that FARDC does not pursue FDLR in earnest, allowing FDLR to come back to retaliate.

The FDLR alleges that the army collaborates with remnants of Maï-Maï Shetani. Unfortunately, this could not be corroborated. MONUSCO has reportedly not been involved in the confrontation. “FDLR has not directly attacked us,” a peacekeeper said. Asked whether UAVs have been active in around Katwiguru, two interviewees said “We have never heard them.”

As for the conduct of the regiment, there were competing accounts. In Nyamilima, interviewees positively remarked on the FARDC: “The army generally behaves well” or “FARDC behaves reasonable in Nyamilima.” In Katwiguru, however, information about reported misconduct of the 107th was reported. While this remains an allegation, MONUSCO is well-advised to probe into the matter. In earlier meetings with the peacekeeping mission, the army’s conduct was descried as “Ok, not a problem, not an issue.”

Resources:

Asked how the FDLR factions are financing their activities, interviewees mentioned a range of options, including illicit taxation, pillaging, hunting, and donations by locals.

Surrenders:

In the areas visited, interviewees did not report on increased surrenders by the FDLR. In all of 2014, MONUSCO reportedly received a mere 25 FDLR elements.This stands in contract to developments elsewhere in the province: On 30 May, 105 FDLR combatants surrendered in Kateku, North Kivu. On 9 June, FDLR surrendered 83 combatants, 225 dependents, 83 light weapons and three heavy weapons in Kigogo (Mwenga territory, South Kivu province).

Shetani:

Following the defeat of its ally M23 in November 2013, the rebel group Maï-Maï Shetani (also called FPD) surrendered en masse in late 2013 and early 2014. In January 2014, the MONUSCO camps in Nyamilima reportedly received 89 Shetani elements led by Col. Jado. Unfortunately, they only surrendered eight arms. The leader Kakule Muhima aka Shetani, currently imprisoned in Kinshasa, is said to have been replaced by Charles Bukande and Maj. Magumu Roger. (Another interviewee reported that a man by the name of Kaserega allegedly replaced Shetani.) Bukande and Roge have reportedly recruited 44 elements (mostly child soldiers) as of late. While this is subject to further verification, it seems very likely that the group is no longer as strong and structured as it used to be during the M23 rebellion.

M23:

As for the M23, stakeholders interviewed did not hear of any large-scale returns, regrouping, or training camps largely because Binza was not a M23-held area.

The Impact of Dodd-Frank and Conflict Minerals Reforms on Eastern Congo’s War

By Fidel Bafilemba, Timo Mueller, and Sasha Lezhnev | Jun 10, 2014

Just four years after enactment of historic Dodd-Frank “conflict minerals” legislation, a new investigative report by the Enough Project identifies early signs of success, with many lucrative mines in eastern Congo no longer controlled by violent armed groups responsible for mass atrocities, rape, and grave violations of human rights.

Market changes spurred by the 2010 Dodd-Frank law on conflict minerals have helped significantly reduce the involvement of armed groups in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (“Congo”) in the mines of three out of the four conflict minerals. The law, in addition to conflict minerals audit programs from the electronics industry and related reforms begun by African governments in the region but not yet fully implemented, has made it much less economically viable for armed groups and Congo’s army to mine tin, tantalum, and tungsten, known as the 3Ts. Minerals were previously major sources of revenue for armed groups, generating an estimated $185 million per year for armed groups and the army. However, artisanally mined gold continues to fund armed commanders. Further reforms are needed to address conflict gold and close loopholes on the other minerals.

Congo-Kinshasa: Minova’s rape acquittals reveal lessons for Congo

By Holly Dranginis and Timo Mueller. Published in AllAfrica on 20 May 2014.

Washington, DC — If Congo and the international community are to learn anything productive from the Minova trial, they will look beyond its verdict. The devil – and the value – is in the details.

Embarking on a renewed peace process, Congo just completed one of its first tests of war crimes accountability: the prosecution of army officers for rape and other war crimes perpetrated in the South Kivu town of Minova. The result is mixed. Of the 39 defendants, 14 were acquitted, 22 sentenced to 10 or 20 years in prison, and two in perpetuity.

Only two were convicted of rape, the rest for pillage and breaking rank. The rape crimes acquittals have spurred disappointment and cynicism, but they should not be equated with failure, just as convictions do not always denote victory.

The Minova trial offers constructive lessons as Congo continues to pursue justice: prosecutors and defense attorneys need more time, coordination, and resources to build viable cases and high-level perpetrators must be stripped of their de facto impunity.

Since proceedings opened in Minova, the case was a beacon of hope.

Widespread sexual violence has persisted unpunished in eastern Congo for decades, leaving physical, psychological, and cultural scars. On the night of November 23, 2012, the Congolese army entered Minova, pushed north from Goma in a state of humiliation by the M23 rebel group. By the next morning, reports emerged that over 200 civilians were raped by army elements.

The Minova trial presented an opportunity to prosecute rape in an environment where impunity reigns. Congolese activists like physician Denis Mukwege and attorney Sylvie Maunga have stressed that justice is critical to stemming Congo’s sexual violence crisis.

With mounting international pressure, authorities agreed to open investigations. But Minova was a Pandora’s box for Congo’s justice system, full of resource gaps, political barriers, and hasty attempts to prosecute complex crimes. Rightly pushed open for the victims of Minova, it revealed just how demanding prosecuting atrocities really is.

In many ways, Minova marks progress. Seventy-six survivors testified despite stigma, threats, and psychological trauma. Authorities provided innovative measures of witness protection. International and community-based organizations, including Physicians for Human Rights and American Bar Association Rule of Law Initiative, played critical roles.

Still, evidence was scarce and prosecutors lacked a coherent, coordinated litigation strategy. Prosecution and defense teams suffered a debilitating lack of resources. As an ex-military prosecutor said, “it’s a weak case … built on a castle of sand.” Some defense attorneys worked for no pay and could not afford the cost of printing, let alone defend their clients effectively.

Prosecutors struggled with the complex task of proving command responsibility, which requires proving there was order among the ranks and commanders had control over troops. Many say that night in Minova was chaos.

Evidence at trial pointed to pandemonium, an utter lack of control by commanders, many of them absentee at the scene. This may not be the whole story.

There may have been more order and control than it appeared at trial because proving command responsibility requires independence from political pressure and time and resources to investigate complex webs of power – luxuries the Minova prosecutors did not have. A case of this magnitude normally requires years but pressure to finish resulted in a rushed, botched effort.

As a result, the recent verdict may send a dangerous message that high-ranking officers and commanders enjoy the protection of a de facto impunity, unreachable by prosecutors confined to short timeframes and low operating budgets.

Finally, the acquittals should not diminish the value of the survivors’ testimony. Their stories lose neither their merit nor their worth because the court failed to identify those responsible for the mass rape. Though some testimony has been called into question, the truth about rape in Congo is emerging due to the survivors who break silence.

Their testimony sheds light on the scope and effects of rape, complementing statistics with valuable human stories.

Congo is currently developing plans for specialized mixed chambers to prosecute other atrocities like those that occurred in Minova. As they do, the government and international supporters should take Minova’s lessons to heart.

As they facilitate the regional peace process, US Special Envoy Russ Feingold and UN Special Envoy Mary Robinson should continue to support the establishment of the chambers. They should press the US and other foreign governments to provide financial and expert assistance, and encourage Congo to allow robust international oversight and the investigation of high-ranking military commanders.

The job of a functioning justice system is to unearth truth through evidence and identify the most responsible perpetrators, regardless of rank or association. Congo has a chance now to break its chronic climate of impunity with transparent, well-resourced, fair trials free of political influence and intimidation.

Clouds over Burundi

Over the recent months, the small landlocked country of Burundi in Central Africa has seen bouts of political violence and restrictions of civil liberties. The worrying developments in one of the poorest countries on the planet prompted the UN Security Council to issue a press statement on 10 April, noting political tensions and encroachments on the press and opposition in the run up to the 2015 elections.

A short historical recap

In the aftermath of the country’s independence in 1962, the Tutsi minority ruled the country for three decades. Following the assassination of President Melchior Ndadaye on 21 October 1993, Burundi was consumed until 2002 by a gruesome civil war during which approximately 300,000 people died. With the signing of the Arusha peace accords in 2000, the country found relative calm. In 2005, the former rebel group CNDD-FDD (National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy) won the multi-party election, turning the old power balance on its head. Pierre Nkurunziza, who was appointed president by the transitional national assembly, failed to deliver on his promises during the 5-year transitional period. He was nevertheless elected in the 2010 elections also thanks to political interference in the electoral process.

A political crisis is unfolding

Since then, political space has been continuously shrinking. Most prominently, on 4 June 2013, the government passed a very restrictive media law. All the while, raptures inside the ruling coalition widened and eventually broke to the fore on 1 February 2014, when President Pierre Nkurunziza sacked his First Vice President Bernard Busokoza, minister of the opposition party Union for National Progress (UPRONA). The conflict is primarily political in nature and should not be reduced to ethnicity.

Following his dismissal and meddling in their internal affairs by CNDD-FDD, three UPRONA ministers resigned in protest, causing the only opposition party in parliament to quarrel and eventually split about their respective replacements. This development led the International Crisis Group on 1 March to conclude in its monthly Crisis Watch that the situation in the central African country had deteriorated.

Then, in early March, 69 members of the opposition party Movement for Solidarity and Democracy (MSD) clashed with the police and were arrested – many arbitrarily – for “armed revolt.” The developments caused UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to express his deep concern on 13 March about the confrontations. A week later, on 21 March, after just one day of trial, authorities sentenced 21 members of MSD to life imprisonment and put another 24 behind bars for other prison terms. Leader of MSD Alexis Sinduhije remains in hiding. The council of Bujumbura later also issued a verdict encroaching further upon the right to peaceful assembly.

The political crisis continued when Imbonerakure, the youth wing of CNDD-FDD, clashed with members of UPRONA in the open. Leaked reports of the United Nations peacekeeping mission in Burundi indicate that authorities have deliberately armed and trained the youth party. Spokesperson of the UN Secretary-General Dujarric clarified that “those responsible for manipulating the youth affiliated to political parties and instigating violence would be liable for international prosecution.” The leakage led to a diplomatic fallout. Denying the accusations, the government retaliated on 17 April, declaring UN Security Advisor in Burundi, Paul Dobbie, persona non grata, giving him 48 hours to leave the country based on his attempts to ‘destabilize Burundi.’

Meanwhile, the crisis continued. Nkurunziza fueled political tensions when he introduced in late March constitutional amendments to remove presidential term limits. The proposal was struck down by one vote only. The fate of Nkurunziza is shared by incumbent presidents all throughout the region. Presidential elections are scheduled in the DR Congo (2016), Rwanda (2017) and Uganda (2016) with Kabila and Kagame unable to run for a new term. (Museveni changed the term limit in 2005). Each President has been fishy about his respective political ambitions.

Compared to its neighbors DR Congo and Rwanda, Burundi receives comparatively little international attention. However, the latest political crisis merits renewed and concerted engagement because it risks to upset the delicate balance in the Great Lakes Region. As Ambassador of the United States to the United Nations Samantha Power said on April 8: “I can’t help but have Rwanda on my mind.”

For further reading on Burundi:

- For a neat overview of developments in Burundi, consult the website of the UN Office in Burundi (BNUD) and reports by the UN Secretary-General.

- Crisis Group and Security Council Report provide sound political analysis.

- For detailed study on the situation of human rights in Burundi, see reporting by the US State Department, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- In-depth reporting by IRIN News.

- To learn more about Burundi’s economy, see studies by the IMF, World Bank, and African Development Bank.

Mining sites in eastern Congo – The most creative names

In late 2013, the International Peace Information Service, or IPIS, updated its mapping of mineral sites in eastern Congo. As the first map of its kind, it shows the location of nearly 800 mining sites and 85 trading centres, including information about armed groups presence and involvement, and the scale of the mining activity. IPIS has provided a short analysis of the data.

Together with my colleague Fidel Bafilemba I recently took a closer look at the map. For one, we were amazed by the creativity of naming mining sites in eastern Congo. Below is a list of our favorites:

- 40-45

- Afrika

- Bahati ya Imbwa (Luck of a dog)

- Benection Divine (Devine benediction)

- Bethlehem

- Camp Avocat (Lawyer’s camp)

- Cesar

- Dieu-Merci (Thanks, lord)

- Disco

- Dubai

- Etas-Unis (USA)

- Geneve

- Gomora

- Israel

- Japon (Japan)

- Jeunes pour jeunes (Youth for Youth)

- Jerusalem

- Kitumba (Dead body)

- Koweit (Kuwait)

- Kurestaurant (To the restaurant)

- La Grace (Grace)

- Lata Bien (Dress well)

- Liberation

- Lumbuzi (Big goat)

- Ma Boutique (My shop)

- Mabele Mokonzi (Soil, the leader)

- Masumu (Sins)

- Mayi ya moto (Hot water)

- Mazarau (Scorn)

- Mbinguni (In heaven)

- Misri (Egypt)

- Monde Arabe (Arab world)

- Mungu Iko (The lord exists)

- Rwanda

- Santa-Maria

- Tusongembele (To go forward)

- Vatican/Kasana

- Vis a Vis